When he was first breaking into the legal weed business in 2011, Joel Pepin did what any sensible, aspiring marijuana entrepreneur would do. He didn’t tell his bank how he was making money.

“You give them an LLC name and you’re sorta vague about the rest, you know what I mean?” Pepin recalls.

He was running a legal business, but if Pepin wanted something as simple as the ability to purchase equipment with a check instead of handing over stacks of cash, he’d have to behave like a common criminal. It’s an uncomfortable legal grey area that continues to afflict most of the businesses within America’s booming marijuana economy—thanks to federal financial rules that haven’t caught up with state-level legalization efforts.

And it’s a struggle to stay one step ahead.

“We had accounts shut down at two different banks,” Pepin tells Reason. “Once you have transactions where there are comments written on the bottom of the checks for ‘wholesale flower’ or that type of thing—they figure out that you’re working in marijuana, and they write you a letter to say you have to pull out your funds and close the account or else they will do it for you in 30 days.”

Things have changed a lot for Pepin since those early days. Today, he’s the co-owner of JAR Cannabis, which has 40 employees, two cultivation facilities, an extraction lab, and two storefronts—along with plans for four more—in Maine, where recreational marijuana was legalized last year.

He’s no longer scrambling from bank to bank, either, thanks to cPort Credit Union, a Maine-based firm that has bucked national trends and has offered banking services to the state’s nascent cannabis industry since 2014. The credit union doesn’t offer loans or financing to marijuana-related businesses, but even the stability of knowing that his checking account won’t be closed next week gives Pepin an advantage over most cannabis entrepreneurs in America.

Medical marijuana is now legal in 36 states. In early April, New York became the 15th state, in addition to Washington, D.C., to legalize marijuana for recreational use by adults over age 21. There were $17.5 billion in legal sales of marijuana last year, but nearly all of those transactions were conducted entirely in cash. Thanks to marijuana’s enduring status as a Schedule I drug, banks that are subject to federal oversight must file Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) each and every time they engage in a transaction with a marijuana-related business—even if the business is fully compliant with state law. The federal law doesn’t prohibit financial institutions from offering banking service to dispensaries and growers, but the added reporting requirements and threat of federal scrutiny keeps many banks away.

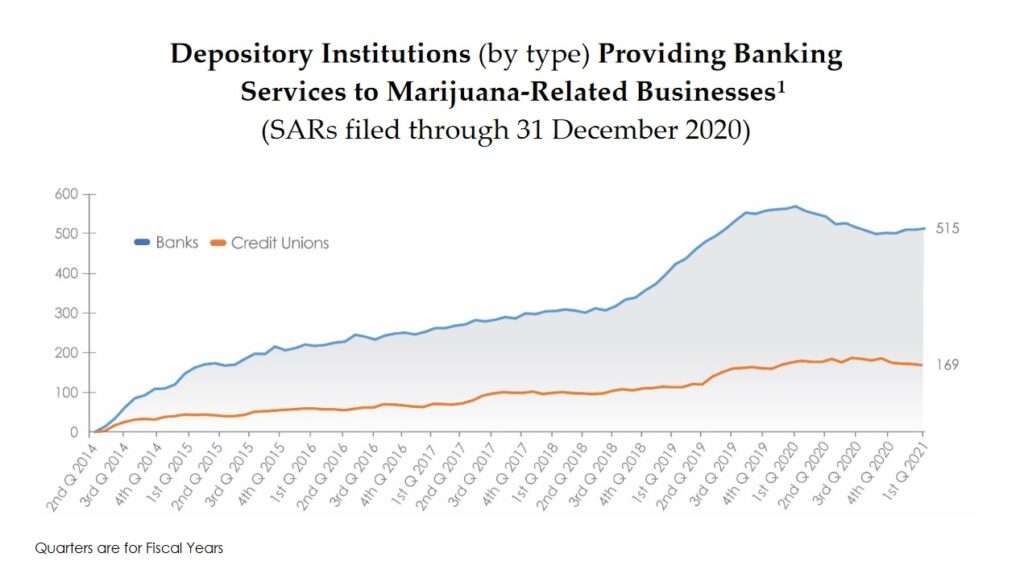

According to FinCEN data, 515 banks and 169 credit unions filed at least one SAR related to a marijuana business during the first quarter of 2021. Both numbers had been steadily growing for years as more states legalized marijuana, but have declined slightly since 2019.

The FinCEN data probably exaggerates how many banks are truly doing business with the marijuana industry, says Morgan Fox, a spokesman for the National Cannabis Industry Association, a trade group. He estimates that the real number is less than one-third of what the federal data would suggest. Because banks are required to file SARs for every transaction that might be related to marijuana, a bank that accepts a single deposit is counted the same way as a credit union that offers its full range of services to a dispensary.

It is hard to get precise figures for obvious reasons, but Marijuana Business Daily, an industry trade publication, estimates that about 70 percent of America’s cannabis industry is operating without any access to even the most basic banking services.

Beyond the fundamentals like having a checking account, processing credit cards, and paying taxes, that means cannabis businesses have a harder time getting access to capital to cover start-up costs or pay for expansions. “For smaller growers, especially, that might mean they aren’t able to keep up,” says Fox. Unless you have a deep-pocketed investor or have been around long enough to build up cash reserves, the lack of banking access means most weed businesses can’t scale up.

This lack of access can also be dangerous. Since many pot shops have to operate as cash-only businesses, they are obvious targets for actual criminals.

“We can’t keep forcing legal cannabis businesses to operate entirely in cash—a nonsensical rule that is an open invitation to robbery and money laundering,” says Sen. Jeff Merkley (D–Ore.), one of 27 senators—including five Republicans—to cosponsor the 2021 version of the Secure and Fair Enforcement (SAFE) Banking Act. The bill would change several federal statutes so banks are no longer pressured to consider state-legal marijuana businesses unlawful. An earlier version of the same bill passed the House of Representatives in 2019 with a bipartisan vote of 321-103, but was blocked by the Senate.

Now that Democrats have full control of Congress, the SAFE Banking Act’s prospects look better than ever. Of course, an even better solution to the federal government’s restrictions on how marijuana businesses can engage in banking would be for Congress to simply order the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) to remove marijuana from Schedule I.

Even for businesses lucky enough to have access to some banking services, like Pepin’s, there would be huge gains from passage of the SAFE Banking Act or the descheduling of pot—not just for the businesses, but for the entrepreneurs too.

“As the owner of a cannabis company,” says Pepin, “I can’t use that income from the marijuana industry to get an auto loan.”

He’s been running a successful, legal business for more than a decade. It’s time to stop treating Pepin and thousands of others like him as criminals every time they walk into a bank.

How Crypto Works?

How Crypto Works?  Why Is Crypto Down? The Truth.

Why Is Crypto Down? The Truth.  Cleveland Clinic Bans Severely Ill Ohio Man From Kidney Transplant Because The Donor Isn’t Vaccinated

Cleveland Clinic Bans Severely Ill Ohio Man From Kidney Transplant Because The Donor Isn’t Vaccinated  LOUISIANA WILL EXPUNGE YOUR CRIMINAL RECORD IF YOU AGREE TO GET VACCINATED

LOUISIANA WILL EXPUNGE YOUR CRIMINAL RECORD IF YOU AGREE TO GET VACCINATED  Kraft Heinz CEO says people must get used to higher food prices

Kraft Heinz CEO says people must get used to higher food prices